(GPR) Global Perspectives and Research: Should Governments Provide Universal Health Coverage

By: Shannen Olivia Chen, BBS Bandung's Class Valedictorian, Batch 2022

The human body is susceptible to numerous diseases. Despite medical advances, human health continues to deteriorate due to climate issues, an aging population, and sedentary lifestyles. A variety of diseases are on the rise, and healthcare services are in higher demand than ever. However, many individuals do not have access to these services due to reasons like geographic and socioeconomic constraints. Thus, many countries are shifting towards a system of universal health coverage (UHC). According to The World Bank, 'UHC is about ensuring that people have access to the healthcare they need without suffering financial hardship.' Other countries that are not currently providing it either do not have the resources or are concerned that it may bring about undesirable consequences. Considering its strengths and weaknesses through economic, cultural, and ethical perspectives, should governments provide universal health coverage?

Following UHC is the prospect of better public health. After Turkey's enactment of the 2003 Health Transformation Program, life expectancy improved to the extent that a Turkish baby born in 2014 could live 6 years longer than someone born before the program in 2002 (The World Bank, 2018) . A similar trend is observed in a longitudinal study from 1995 to 2008. Considering the statistics in 153 countries, it was found that a 10% increase in government spending on UHC would decrease women's mortality rate by 1.6 deaths for every 1000 people. In contrast, a 10% increase in out of pocket payments led to an increase of 11.6 out of 1000 female deaths (Moreno-Serra & Smith, 2011). These findings were representative of the trends established in the study, meaning that UHC not only has the potential to cause immediate drastic improvements like what occurred in Turkey, but its expansion would also allow for a continuous refining of population health in the long run. Thus, governments should consider UHC to be an investment with health benefits that would last and even improve over many generations.

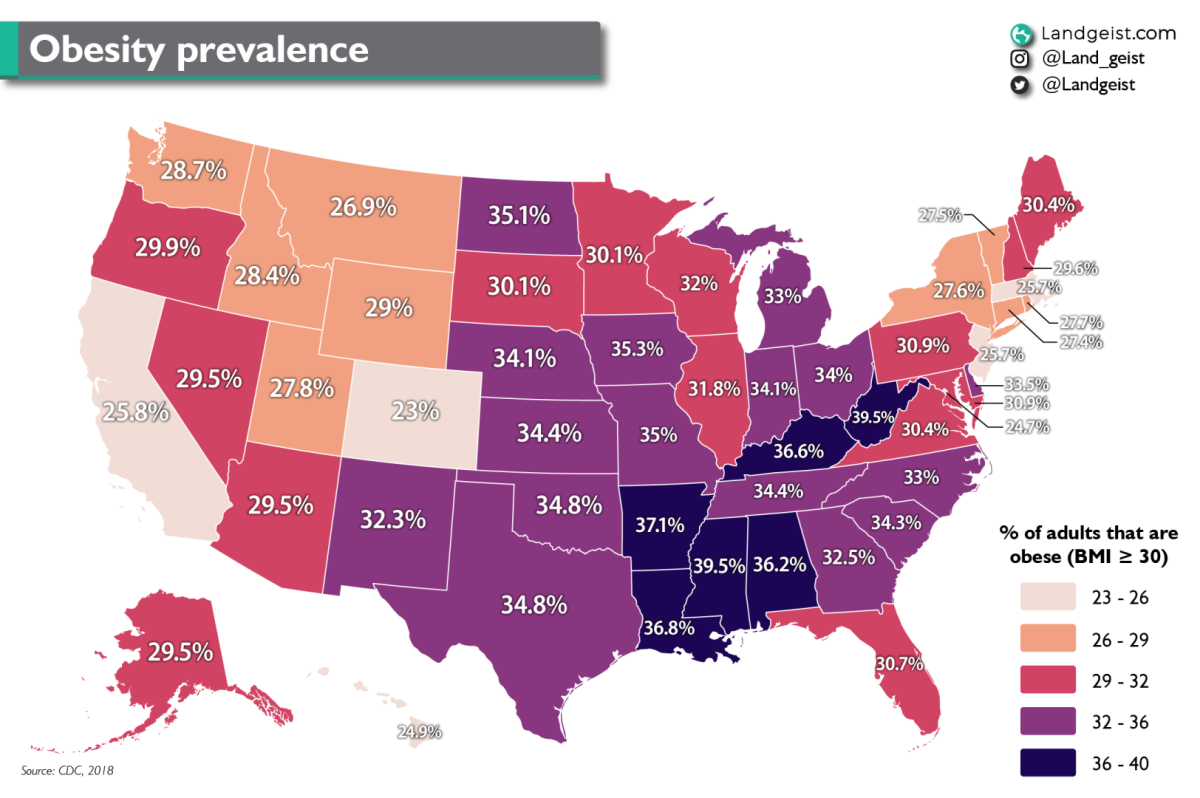

One of the reasons why UHC is so widely advocated for, is that it would save lives at a lower cost. Out of the 33 developed countries in the world, the United States (US) stands as the only one without UHC. Among the 11 OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) countries, US citizens have the lowest life expectancy, an obesity rate twice that of the average, and are most in danger of chronic diseases (The Commonwealth Fund, 2020). In spite of this, it is alarming to see that they spend the most on healthcare per capita than in any other country, spending 16.9% of their GDP. In comparison, healthier countries like New Zealand spend approximately half at 9.3%. This is due to lower administrative and clinical costs, the lower price of pharmaceutical goods, and a salary cap brought about by UHC. If the US were to implement a UHC system like Medicare, 68,000 lives and $450 billion would be saved annually (The Lancet, 2020).

In contrast, Thailand was able to develop a form of UHC in 2001 despite being a developing country. Medical bills were subsidized to the extent that patients would always pay less than 30 baht or 0.99 USD per hospital visit. Following its implementation, child mortality fell to a low of 11 per 1,000 people in both prosperous and impoverished areas (Harvard Public Health Review, 2015) . The contrast between the US and Thailand shows that a larger expenditure on healthcare does not always correlate to better public health. In fact, a cheaper system of UHC would successfully improve the health of many, like what was observed in Thailand. With a solid implementation of UHC, citizens would be able to save more money and governments would have a higher budget to further improve healthcare.

Universal healthcare has also been shown to effectively reduce inequality and promote economic growth. After the Second World War, pressures such as industrialization and competition led Japan to develop a system of UHC even before they became an economically developed country. In 1956, Prime Minister Kishi highlighted the importance of the implementation of a welfare state to ease Japanese citizens' conditions of unemployment and disease. Having sent experts to perform thorough analysis on his country's situation, he acknowledged that universal healthcare was a key component of a broader attack on problems of economic inequality that had emerged. Indeed, an egalitarian pattern had been well established, ensuring social stability through the equitable distribution of the benefits of economic growth across the population in a people-centered development (World Bank Group, 2014). This lesson from Japan shows us that once healthcare universality is achieved, people will have the same access to medical services regardless of their status. This proves that good health allows people to work more efficiently and effectively, improving economic productivity as a whole.

On the contrary, one of the reasons why UHC is still not implemented in some countries is the issue of doctor shortages (World Health Organization, 2011). As of 2019, 18 million health professionals are lacking worldwide, especially in areas prone to diseases like Sub Saharan Africa. If countries are to deliver UHC to everyone, 1 in 4 jobs would need to be in the healthcare sector by 2030 (Oluga, 2019). Having an adequate doctor to patient ratio is the backbone of fulfilling the UHC objective of providing healthcare access to everyone. Without enough clinical workers, there would be no one to cater to the needs of many patients, and universal coverage would be impossible. From this, we can see that implementation of UHC is already challenging. What more the problems to be encountered after its execution?

Alleviating inequalities is one of the objectives of UHC, but it has been argued by UN Women to not consider other barriers apart from income and wealth, such as disadvantages due to ethnicity, gender, disability, and widowhood in achieving an inclusive healthcare system. The government should not merely focus on poverty, but to take into account social factors and power relations that are preventing equal access to healthcare (Sen, et al., 2020) . A system of UHC may remove some economic barriers, but does not tackle the root social causes behind marginalization and exclusion in healthcare. A 2005 study by the Arizona State University reports that, 'contrary to what most people believe, the tendency to be prejudiced is a form of common sense, hard-wired into the human brain through evolution as an adaptive response to protect our prehistoric ancestors from danger'. The fact that the issue has long been present makes it likely that social prejudice is inherent in society. Thus, it is unlikely that merely providing health insurance would eliminate discrimination in healthcare. UHC may alleviate the fiscal barriers, but inclusivity cannot be achieved if social barriers between groups are not removed.

Moreover, the lack of consideration of unexpected events like the COVID-19 outbreak has led to many problems for some UHC implementing countries like Indonesia. BPJS Kesehatan, Indonesia's healthcare insurance program, has been covered 222.38 million individuals as of March 2020. National law states that the government is responsible for paying for the healthcare of citizens during times of disaster, including pandemics. This means that the ministry is expected to bear all the medical bills incurred in the treatment of Covid-19 patients (Gorbiano & Akhlas, 2020). As a result of underpriced premiums, BPJS Kesehatan is now IDR 14 trillion (USD 959 million) in debt to hospitals (Nurbaiti, 2020). Similarly, the reason why UHC is not implemented in the US is that UHC enactment is estimated to contribute to an additional $19 trillion in debt, rising the percentage debt of GDP from 74% to 154% by 2026 (Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, 2016). Such an economic strain would also burden individual citizens, as most UHC systems are funded by the taxes people pay. As of 2013, the average payroll tax in the US is 15.3%, while European countries with single payer systems pay 37%. In order to fund a similar system, Americans would have to double the payroll taxes they pay (Gregory & Roderick, 2003). As we can see from Indonesia, UHC is very expensive to implement and significant funds could have been saved during the Covid-19 pandemic had the system not exist. What is even more striking is that UHC would also be a financial burden to developed countries like the US. Large reserves would be needed to maintain the system, and there is no guarantee that the potential benefits of UHC would outweigh its projected costs.

It is argued that people should be responsible for their own health, especially since diseases are often preventable. Evidently, 6 out of 10 leading causes of illnesses are preventable. These include unsafe sexual intercourse, high blood pressure, alcohol use, high cholesterol, obesity, and tobacco use (Journal of Medical Ethics, 2007). This suggests that, if health is determined by lifestyle choices, then those who make better decisions shouldn't be paying higher taxes for services used by those who are irresponsible of their bodies. Instead of improving population health, affordable treatment due to UHC may be seen as a safety net, encouraging people that they will be cared for even if they neglect their well-being and fall ill. If people can choose to be fit, prevention of diseases and education of better lifestyle choices would be more effective than UHC in sustaining a healthy population.

This study has further strengthened my initial belief in the benefits of UHC, since I now understand that it has the potential to improve public health with the use of lower expenses in the long term. Since healthier people are more productive, UHC would allow a country to develop as a whole. As long as a country has financial stability, an adequate doctor to patient ratio and enough preparation for any possible unprecedented events like the Covid-19 pandemic, a system of UHC would sustain a healthy and thriving population for generations to come.

However, if UHC is so beneficial, I wondered why some countries chose not to implement it. I used to think that this is only due to financial limitations, but I did not understand why even a developed country like the US favors private health bills. Through this research, my eyes have been opened to see that what works for one country may not always work for another. Without the right policies, resources, and priorities, a system of UHC may instead lead a country into debt and chaos. If people can choose to live a healthy lifestyle, UHC may instead be a counter-productive program and cause citizens to no longer be responsible for their own health. Furthermore, inequalities in healthcare are rooted in the way society is constructed, and UHC is unlikely to remove the underlying reasons why health discrimination still exists. I now believe that there is no one size fits all model for healthcare systems, and UHC is certainly not always the best way for governments to invest in healthcare.

Thus, I suggest conducting further research on alternatives like health education, pollution reduction, and housing provisions. Only after comparisons with these alternative strategies, will we be able to achieve a holistic view of whether or not governments should implement UHC. Other areas to also be considered are the effects of UHC implementation on drug quality and machine use, and how the UHC may lead to more ageing populations. UHC is a strategy that requires thorough evaluation, and the list of other future research possibilities is infinite and certainly not limited to those mentioned above.

Bibliography

Journals

Harvard Public Health Review, 2015. Universal Healthcare: The Affordable Dream. [Online]

Available at: https://hphr.org/5-article-sen/

Journal of Medical Ethics, 2007. Responsibility for health: personal, social, and environmental. [Online]

Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2598168/

The Lancet, 2020. Improving the prognosis of healthcare in the US. [Online]

Available at: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(19)33019-3/fulltext

Reports

Moreno-Serra, R. & Smith, P., 2011. he Effects of Health Coverage on Population Outcomes : A Country-Level Panel Data Analysis. [Online]

Available at: https://r4d.org/resources/effects-health-coverage-population-outcomes/

World Bank Group, 2014. Universal Health Coverage for Inclusive and Sustainable Development - LESSONS FROM JAPAN. [Online] Available at: http://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/263851468062350384/pdf/Universal-health-coverage-for-inclusive-and-sustainable-development-lessons-from-Japan.pdf

World Health Organization, 2011. WHO Global Code of Practice on International Recruitment of Health Personnel. [Online] Available at: https://www.who.int/workforcealliance/knowledge/resources/PAK_ImmigrationReport.pdf

Online Publications

Arizona State University, 2005. Prejudice Is Hard-wired Into The Human Brain, Says ASU Study. [Online] Available at: https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2005/05/050525105357.htm

Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, 2016. Adding Up Senator Sanders's Campaign Proposals So Far. [Online]

Available at: http://www.crfb.org/papers/adding-senator-sanderss-campaign-proposals-so-far

Gorbiano, M. I. & Akhlas, A. W., 2020. COVID-19 exposes flaws in Indonesia's health insurance program. [Online]

Available at: https://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2020/04/08/covid-19-exposes-flaws-in-indonesias-health-insurance-program.html

Gregory & Roderick, P., 2003. Obamacare A Mess? Liberals Say Go Single Payer.. [Online]

Available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/paulroderickgregory/2013/10/28/obama-care-a-mess-liberals-say-go-single-payer/?sh=4a18e80228a0

Nurbaiti, A., 2020. Govt officially annuls national health insurance premium hikes in April. [Online]

Available at: https://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2020/04/22/govt-officially-annuls-national-health-insurance-premium-hikes-in-april.html

Oluga, D. O., 2019. Invest in the Health Workforce: That is how we keep the UHC promise. [Online]

Available at: https://www.healthworkersforallcoalition.org/features/2019/12/11/invest-in-the-health-workforce-thats-how-we-keep-the-uhc-promise

Sen, G., Govender, V. & El-Gamal, S., 2020. Universal Health Coverage, Gender Equality and Social Protection: a Health Systems Approach. [Online] Available at: https://dawnnet.org/publication/universal-health-coverage-gender-equality-and-social-protection-a-health-systems-approach/

The Commonwealth Fund, 2020. U.S. Healthcare from a Global Perspective, 2019: Higher Spending, Worse Outcomes?. [Online]

Available at: https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2020/jan/us-health-care-global-perspective-2019

The World Bank, 2018. Turkish Health Transformation Program and Beyond. [Online]

Available at: https://www.worldbank.org/en/results/2018/04/02/turkish-health-transformation-program-and-beyond

The World Bank, 2021. Universal Health Coverage. [Online]

Available at: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/universalhealthcoverage#1